Time signatures are the numbers you see at the start of any piece of sheet music.

They look like fractions but looks can be deceiving!

Let’s take a look at what time signatures are and how they affect your songwriting!

What Are Time Signatures

Time signatures tell you two important things: how many beats are in a bar (or measure) and what type of beats they are.

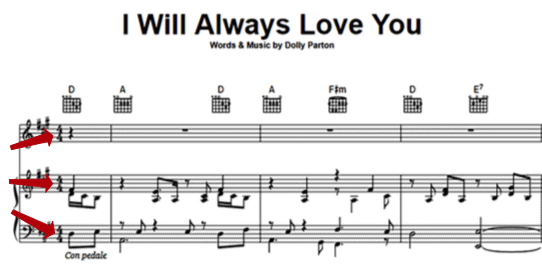

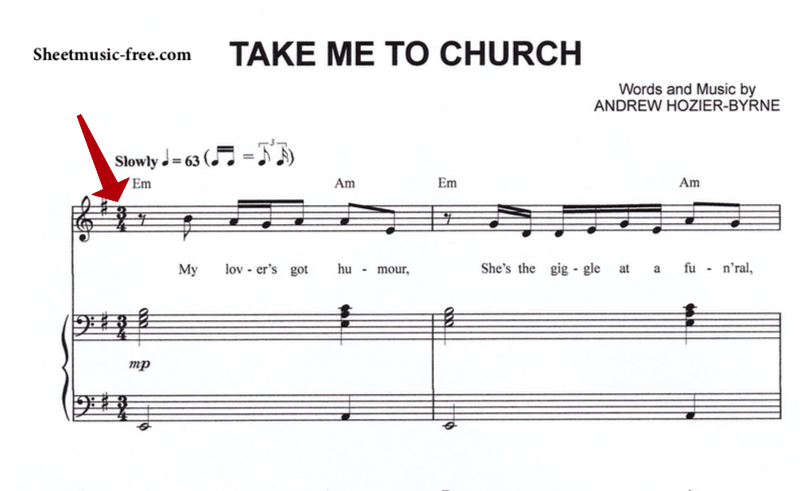

Here’s a Dolly Parton song in a sheet music arrangement for voice, piano or keyboard, and guitar. You can see right at the start, in all three parts, there are two numbers stacked on top of each other that look like this:

The top number (4) tells us how many beats are each bar. In this case, four.

The bottom number (also 4, here) tells us the type or rhythmic value of each beat.

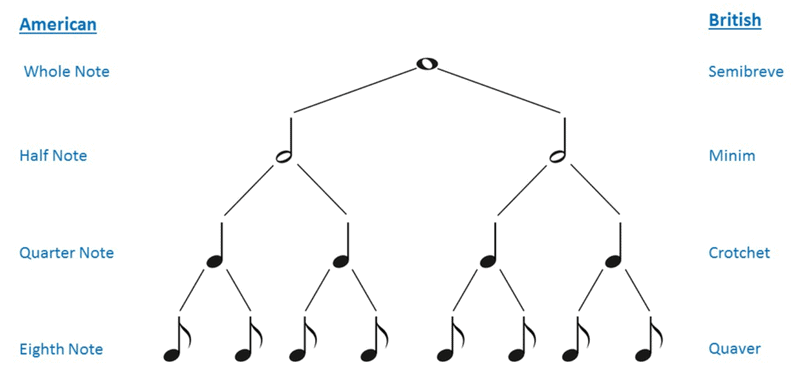

These beats are crotchets or quarter notes. Here’re the most common note values in both UK and US terminology.

So Dolly’s hit has four quarter notes in each bar. In conversation, you’d say, “It’s in four-four.”

This is by far the most common time signature in contemporary recorded music. In sheet music, you’ll sometimes see it written just “C” for “Common.”

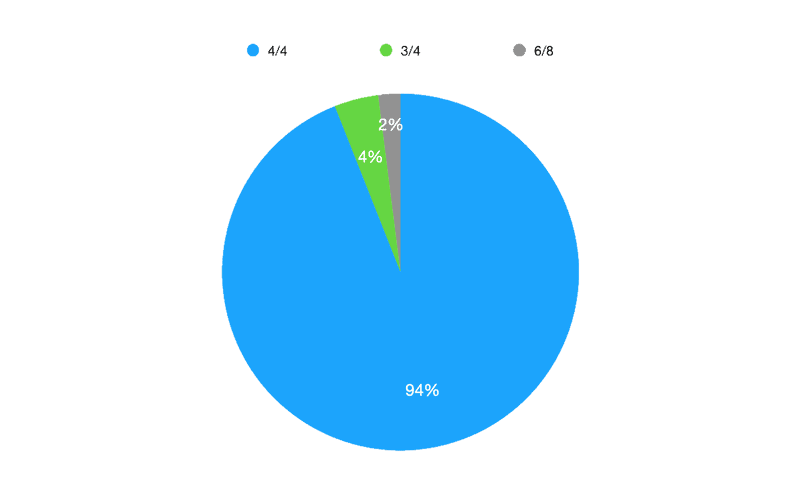

Here’s just how common it is:

This data comes from a study of #1 hits in Australia. They took the most popular #1 hit for each year from 1960 to 2011. And 94% of them were in 4/4!

This is echoed in a 2018 study of songs in the Billboard Top 5.

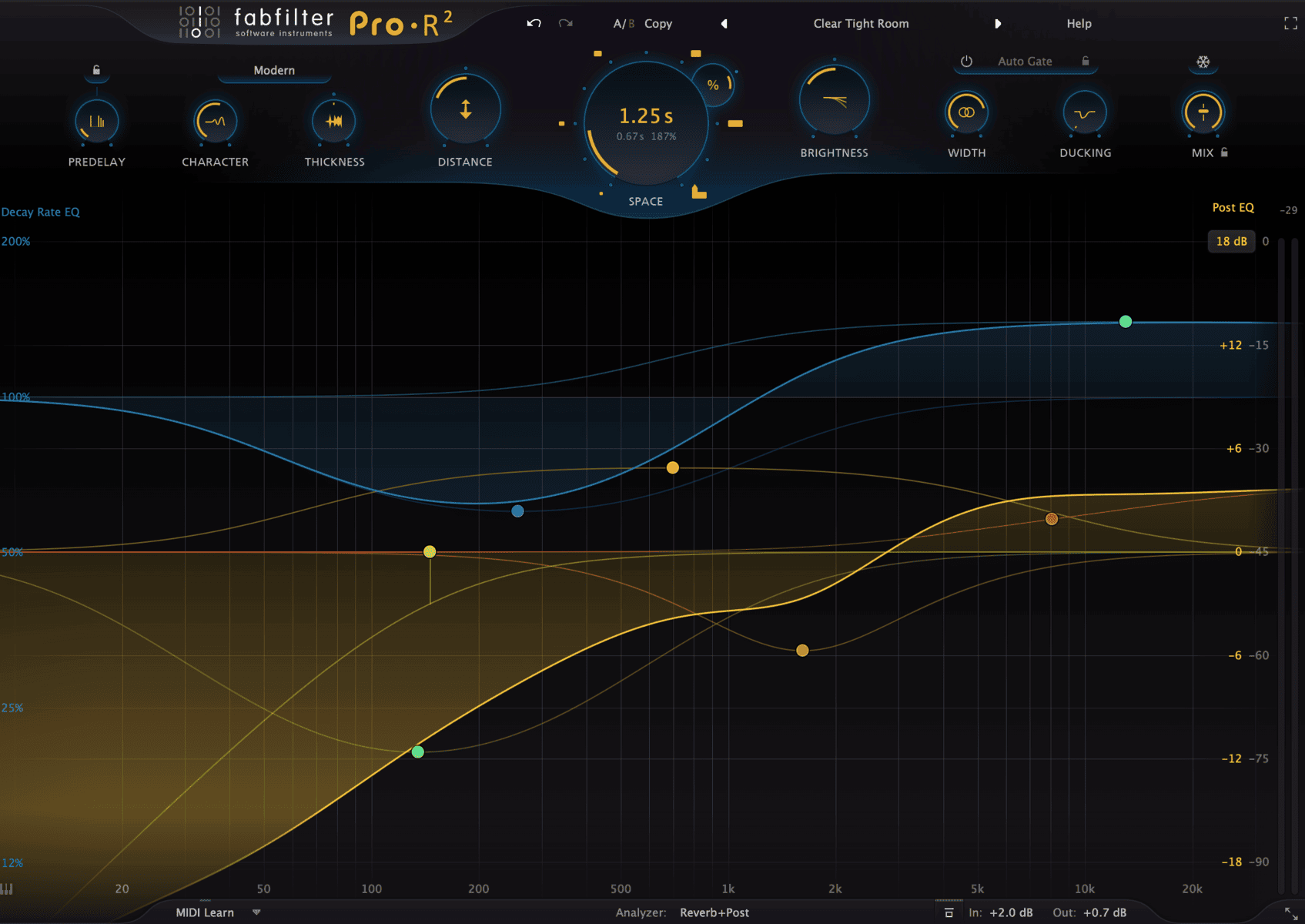

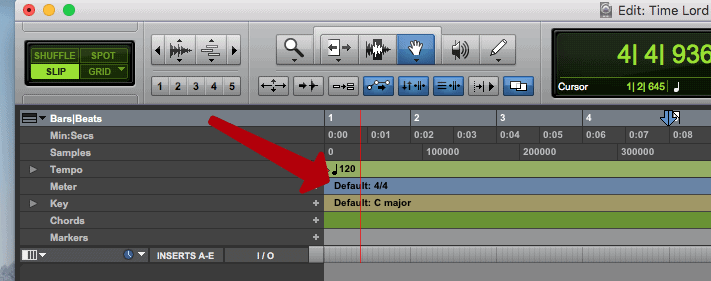

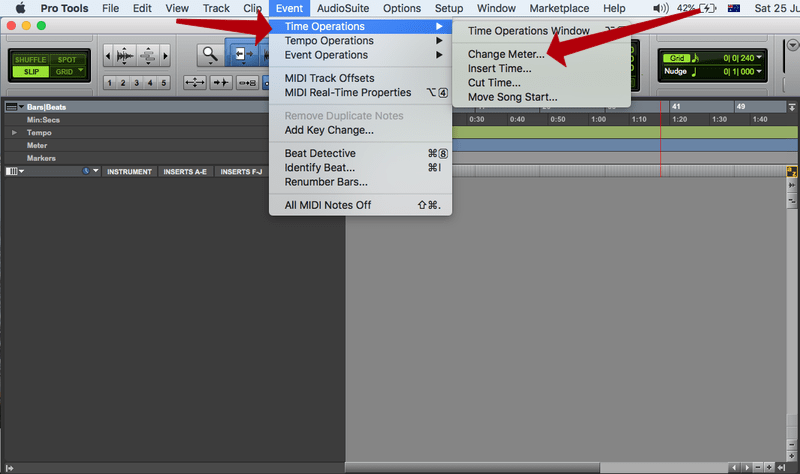

The time signature 4/4 is so common, it’s the default option in every DAW you open. Here’s mine in Pro Tools.

You might notice the numbers aren’t stacked on top of each other. Instead, they are now presented horizontally with a slash between.

It makes the time signature look even more like a fraction… but it’s still not.

The term meter is used here instead of time signature, but it means the same thing.

Using Time Signatures

A couple of useful pointers when working with time signatures

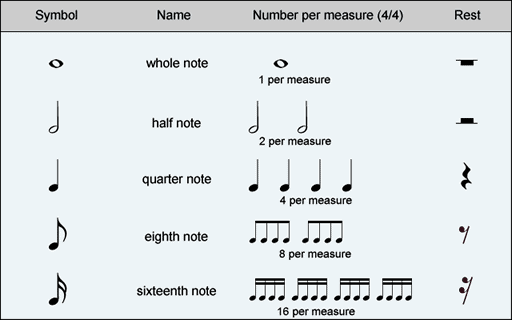

1. Each bar has to add up

All note values (including rests) should add up in each bar.

In the time signature 4/4, it doesn’t matter if you use four quarter notes or two quarter notes plus a half-note rest. Or even eight eighth notes.

You just need to have a total value of four quarter notes in each bar.

2. The time signature has nothing to do with the tempo or bpm

It’s telling you how the rhythm of the song is organized, not the speed.

Two other helpful terms that come up are the downbeat and the backbeat.

The downbeat is the first beat of the bar, sometimes called the one.

It’s important in songwriting because this beat is often accented rhythmically. Especially by the kick drum and bass.

You lean on it.

It’s a great place to put the important notes in the melody. And the strongest words in your lyrics, particularly in the chorus.

The backbeat is the third beat of a 4/4 bar. Not as accented as the downbeat, it still has a push.

We hear the snare drum land on 3 very often.

So 1 2 3 4 becomes more like:

![]()

Other Time Signatures

Let’s check out some less common time signatures that can still be super handy!

Three-Four

The next slice of the time signature pie contains songs in 3/4. It became hugely popular as a dance craze in the nineteenth century: the waltz.

Roughly 4% of the time, you’ll hear it used in popular music today. Often in country, alt country, and folk.

But here’s one that screamed up the Billboard charts.

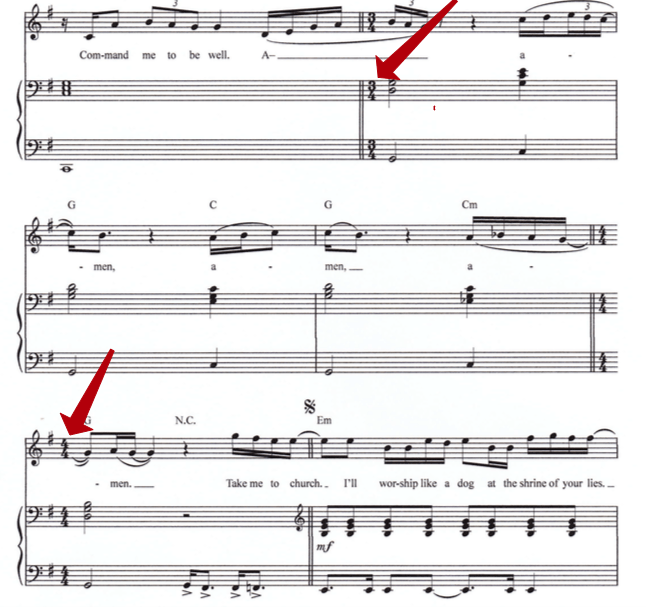

This song is also unusual because, while the verse is in 3/4, it changes meter at the prechorus to 4/4.

This raises another point. Just because a song starts in one time signature, it doesn’t have to stay there.

Using a new time signature lets musicians know when to change the count and to what. It’s the songwriter’s prerogative though, and it helped “Take Me To Church” stand out from the 4/4 crowd!

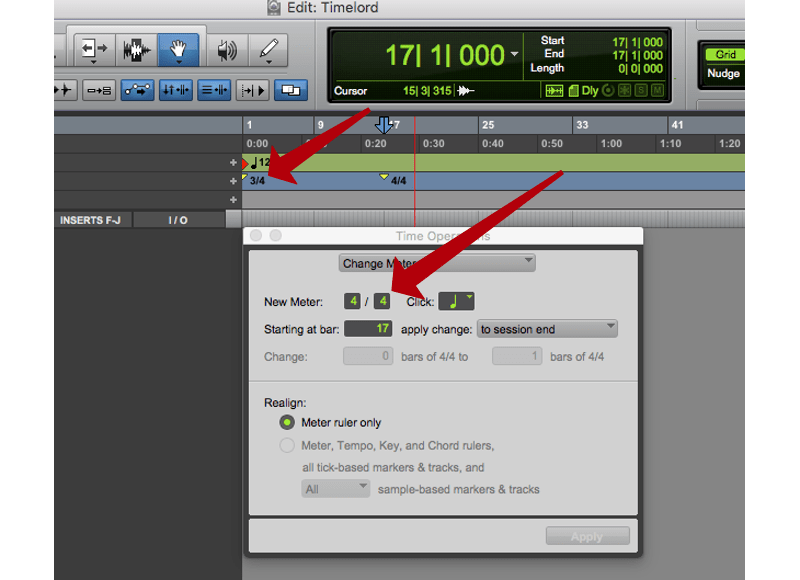

You can try changing time signatures in your DAW by opening the Time Operations Window (in the Events Menu) and accessing Change Meter.

You can then determine how many bars you’d like to try at 3/4 before switching time signatures back to 4/4. Or the other way round!

Time signature is another important lever to manipulate in your songwriting journey.

My advice is to experiment and then make sure any transitions in meter are really solid.

Shifting the number of beats in the bar within a song is a real pull on the listener’s sense of groove. The most repetitive part of a song.

Use with care!

Six-Eight

The first two time signatures we’ve looked at are the very popular 4/4, or common time, and 3/4.

The final slice of the time signature pie is related to 3/4. It slightly differs because it is a compound time signature.

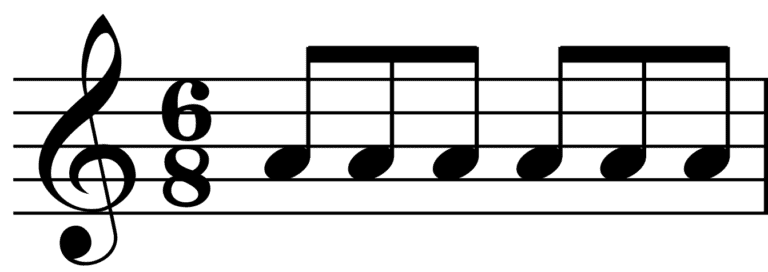

The top number 6 means there are six beats in the bar and the bottom number tells us their value, eighth notes.

But in compound time signatures, the rhythm of notes and rests is organized in multiples of 3. They count triplets.

So 6/8 sounds like two groups of eighth note triplets.

You can see this when people sway side to side in a song with a 6/8 time signature, with accents on the 1 and the 4. Like in “The House of the Rising Sun.”

123 456

That’s why the drummer on The House on Cliff’s cover of this classic song counts in with a “1, 2.” He’s counting in the two groups of triplets to his bandmates.

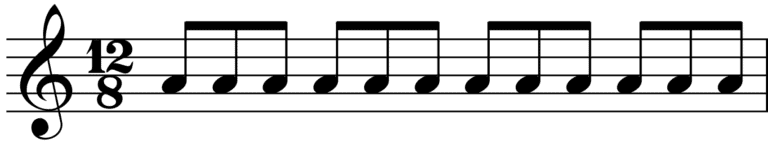

Another compound time signature is used in Lou Reed’s song “Perfect Day.”

This uses 12/8, or twelve beats of eighth notes to each bar.

We hear it as four groups of triplets. Listen for this played on the high hats, with accents on beats 1, 4, 7, and 10 in the bar.

This time signature is the beloved backbone of southern soul music. It’s currently sneaking into the charts through R&B artists.

Irregular Time Signatures

An honorable mention goes to songs that use irregular time signatures. They’re marked by odd numbers of beats per bar that are indivisible.

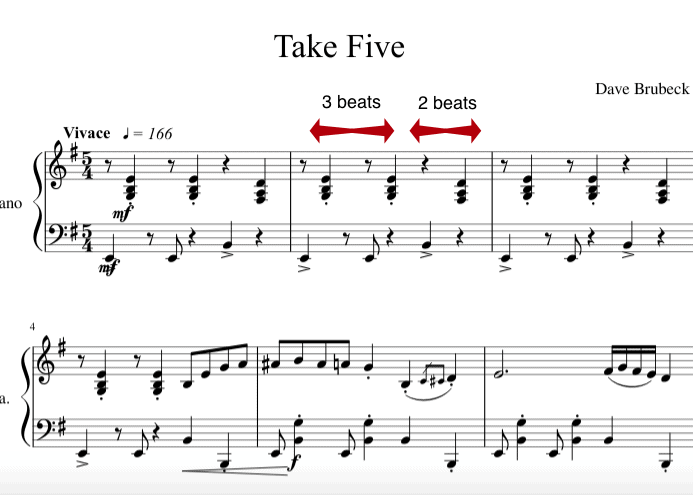

Here’s an example:

This uses five quarter notes per bar and was made famous through Dave Brubek’s hit jazz song “Take Five.” Watch the drummer set the groove up.

Irregular time signatures are a mix of simple and compound time. This signature splits the five beats into a group of three and a group of two quarter notes.

Another example is Pink Floyd’s 1981 hit “Money.”

It uses an irregular time signature of 7/8. And you can hear this set up with cash register samples in the groove at the front.

The song later switches to 4/4, but this use of an irregular meter underpinned the song’s unsettling message.

Conclusion

This is a brief overview of time signatures and how songwriters can communicate about rhythm more effectively.

Using different meters is also a way to make a song extremely distinctive. And it’s another production lever to pull.